The earliest references and iconography of morris dancing and its ancestor, ‘moresk’ dancing, indicate that the pipe and tabor provided the music.

In the early 15th Century, moresk was a fashionable entertainment in courts across Europe. It consisted of exotic dancers from Asia, Africa and the Middle East, dancing wildly to the pipe and tabor. At this time the taborer was a common sight in court and civic circles, providing music for dance, entertainment and processions.

During the latter part of 15th Century it seems that a number of moresk derivatives

appeared, not performed by exotic dancers from other lands, but by trained dancers from the court environment. The music remained on the pipe and tabor.

In England the moresk evolved into morris dancing and by the 18th Century had similarities to the morris that we know today. Pipe and tabor remained the primary instrument for morris, even though in other realms of music it was losing ground against more ‘sophisticated’ instruments.

By mid 19th Century, the number of taborers was on the wane. As the old musicians died, no-one new was taking up the instrument. Some morris sides shared their taborer with other sides whilst others recruited musicians playing more modern instruments, like the fiddle and concertina. However, the dancers were known to prefer the pipe and tabor.

Traditionally the taborer leads with the tabor, playing a rhythm that relates directly to the footfalls of the dancers, something that the primarily melodic instruments like the fiddle could not do so easily.

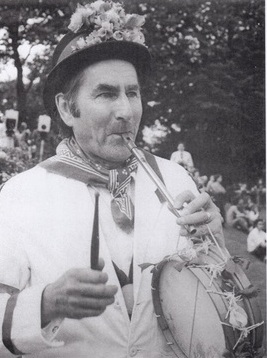

At the end of the 19th century, morris and its music had all but disappeared, and a few years later WWI wiped out many of the remaining teams. The last remaining morris taborer was Joe Powell of Bucknell. Joe played a short ‘D’ tabor pipe and a small shallow tabor.

In the 1920s Powell was visited by leading figures in the morris revival, notably Russell Wortley and Kenworthy Schofield. Both were inspired to revive the tradition of taboring.

Wortley developed a style closely aligned to the morris taboring tradition of beating on the footfall. He favoured the shallow tabor and the short pipe.

Kenworthy Schofield incorporated ideas from early music and the continent to create a new style and indeed, a new instrument. The tabor he played came from the Basque country. It is a deep tabor, approximately 10” x 10”. He asked a fellow dancer from St Albans Morris to help him develop a new low pipe in brass. Kenworthy’s taboring style had a distinctive regular pattern as opposed to the ‘footfall’ approach of Wortley.

Here is a beautiful, but sadly silent film of Kenworthy Schofield playing for the St Albans Morris Men in 1950 in Berkhamstead High Street:

http://www.eafa.org.uk/catalogue/1691

A recording of Kenworthy playing tunes for rapper dance

http://folklore.bc.ca/jigs-for-rapper-sword/

Both of these men inspired others to play and soon there was a demand for pipes and tabors. Wortley worked with Barnes and Mullins to launch a low cost ‘D’ pipe based on the Generation tin whistle. Dancers from St Albans Morris started their own production of instruments on the Schofield pattern. David Turner made plated brass copies of Schofield’s pipes, then Jim Jones started making the new versions in stainless steel. Bill Warder made the tabors – both deep (Basque pattern) and shallow (English pattern). After Bill’s untimely death, tabor production was taken up by Mike Chandler.

Since the 1970s, Bert Cleaver and Mike Chandler have pioneered the Schofield style and it has become the mainstream of morris taboring style. However, despite its authentic heritage, it is no longer the a popular instrument for morris, these days the melodeon leads the way, followed by the anglo-concertina, accordion and fiddle.

Jim Jones gave up making the Schofield pattern pipe because of arthritis but Russell Wortley’s Generation Pipe is still in production. Mike Chandler is still making tabors based on Schofield’s Basque instrument.

Steve Rowley 2007

Click here for more information about Joe Powell – The last traditional morris taborer.